Just one more subsidy, bro

The great UK venture bailout, part 94.

Introduction

UK pension funds have become the scapegoat of choice for politicians and investors. The industry delivers poor returns by international standards and has been repeatedly accused of pursuing an overly-cautious allocation strategy that has resulted in a shortage of private capital for innovation.

Last week, the government unveiled its Pensions Review, which brought together a number of long-anticipated reforms. These include mandating all multi-employer defined contribution (DC) pension schemes to offer at least one default arrangement (the investment strategy that members are automatically placed into) with £25 billion in assets under management (AUM) by 2030. It also reiterated an earlier commitment from funds to invest at least 10% of assets in private markets, including at least 5% in UK private assets by 2030. The government has announced that it will legislate to give itself the power to force funds to comply if they miss this target.

There’s plenty in the review to unpick, much of it is sensible.

Defined Contribution (DC) pensions are the default for most UK workers. In these schemes, individuals and employers contribute a percentage of salary into an investment fund. The value of each saver’s pot rises or falls with the performance of the underlying assets.

The UK DC market is unusually fragmented. At the start of 2023, the UK DC landscape had almost 27,000 DC schemes, of which over 25,000 had fewer than 12 members. In Australia, the top five superannuation funds account for over 30% of assets; in the Netherlands, most workers are covered by a handful of large industry-wide schemes. By contrast, small UK schemes lack the scale to operate. Consolidation is likely a good thing.

However, the UK and venture mandates strike me as an attempt to commandeer long-term savings for a short-term bail out of UK capital markets, which risks leaving everyone, bar an army of middlemen, worse off. These mandates are my focus today.

A good deal for fund managers, not for savers

In the past, I’ve expressed my scepticism about the idea that there is a big gap in the UK venture market that the government needs to help plug. I suspect market size is the real structural problem for European tech and that the government backstopping venture is largely displacement activity.

Luckily, the review’s authors have focused on the benefits for savers of its proposals, namely better returns and lower fees.

In the impact assessment, the review states that ‘a range of evidence suggests scale could deliver over 10 basis points reduction in fees’.

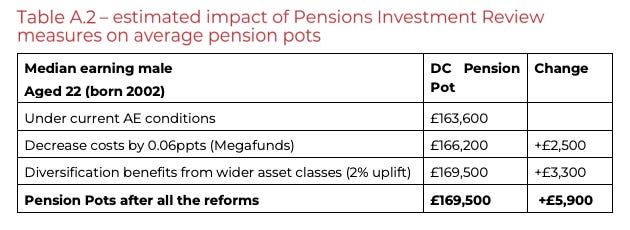

Government clearly considers this to be optimistic, because the worked example in the document only assumes a 6 basis point cut in fees, trimming the annual charge from 0.3% to 0.24%. Over a full 46-year career, this adds £2.5k to the median earner’s pot.

As far as I can tell, however, this calculation doesn’t factor in the higher fees associated with the private assets the government wants pension funds to invest in. Typical venture capital or private equity structures charge 1.5-2% plus 20% carry on gains. Even if only 10% of the fund goes into these assets, the blended fee increases by about 15 basis points, more than double the consolidation saving. If the pension funds decided to downweight venture in favour of other private assets, it could be closer to 10-12 (but still significantly more than 6). While the pension fund rather than savers technically pays these fees, the costs will obviously be passed on.

Bizarrely, the report actually acknowledges that these vehicles “might have higher upfront costs”, but then doesn’t factor them into its analysis. Maybe the government is hoping that scale will help here. It’s true that private equity has been successfully squeezed on fees in recent years, venture fund fees vary comparatively little. Top-tier funds that don’t struggle to raise also know that they’ll be able to hold the line.

The government throws in a 2% uplift to the final pension pot to account for the benefits of diversification (although the number itself seems arbitrary). However, a single 2% bump cannot compensate for bigger fee drag every year for four decades, unless private-market returns consistently outperform public markets (after fees and carry) at a rate unheard of in UK history.

Even if it were possible to chisel a few more basis points off the fees, this still wouldn’t amount to an argument for investing more in private assets. If there is an argument, it’s that higher returns justify the higher fees. But how consistently do we see these higher returns?

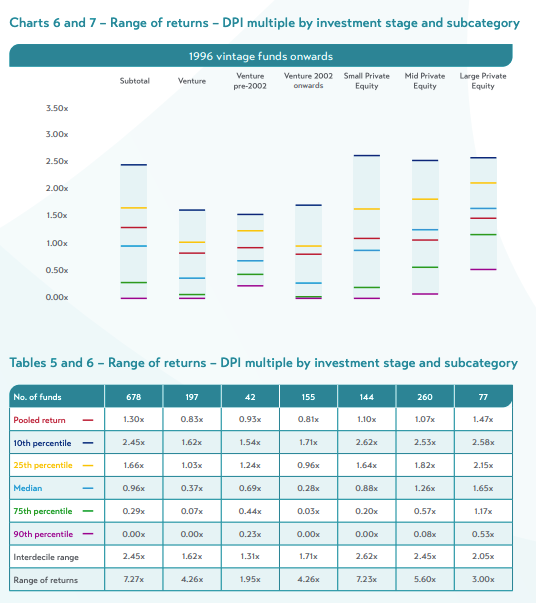

Venture is an unforgiving asset class. While the top decile of funds deliver genuinely impressive performance, the median fund … does not. Depending on how charitable you are with your start year, the median UK venture fund has underperformed a passive UK equities ETF by one to three percentage points per year, while requiring investors to forego liquidity. Even these gains are primarily driven by unrealised valuations that may yet never materialise.

As the single biggest investor in UK venture funds, the UK Government (read: the taxpayer) has subsidised this meagre track record to the tune of billions while enriching a caste of fund managers. These subsidy schemes were, in fact, the subject of my first ever post on Chalmermagne.

The limits of scale and stickiness

At this point, the obvious answer might be to allocate to the good funds and not the bad ones, leading to an industry clear out.

UK pension funds are currently pretty unpracticed at allocating to venture – it’s not the same skill as buying regulated utilities or investing in infrastructure projects. Historically, they’ve been unwilling to pay for the salaries required to hire talented investors or have tried to swerve fund fees via direct investment. But even if we make the (doubtful) assumption that UK pension fund managers could become the world’s smartest allocators overnight, there are several obstacles.

Firstly, there is only so much capacity. The top funds are chronically oversubscribed, sometimes by as much as 3x - 5x. Allocations will go to existing investors first. Flagship venture funds may only accept low tens of millions from all new investors combined – a drop in the ocean for a large auto-enrolment pension scheme.

The funds could just grow bigger, but scaling funds beyond a certain size structurally degrades their ability to generate an outsized return. This is because there is a finite number of good opportunities.

To justify a decade of illiquidity, a venture fund traditionally targets a minimum 3x net return. A £500 million fund can hit that if one £10 million deal turns into a £1 billion exit. By contrast a £2 billion fund needs four such deals. This is challenging in the US, with the world’s largest economy and most mature technology ecosystem. It is implausible for a single fund to achieve this in the UK – simply because a smaller market size logically entails a smaller talent pool. For example, just how many sales leaders are there in the UK who can take a company from £5 million ARR to £100 million and beyond?

Big US venture funds like a16z, Thrive, and General Catalyst are already pivoting into different asset classes (like traditional private equity or public equities), precisely because they are struggling to spend the huge piles of money they’ve amassed.

Secondly, stickiness is limited. In venture, roughly 30% of the funds ranked top-quartile in one vintage slip to median or worse in the next. This could be down to team churn, strategy drift, bad luck, or any other number of possible factors. Only the extreme edge consistently beats public markets. In traditional private equity, persistence rates are even lower.

In short, there isn’t a crack team of people we can just hand the money to, even if they had the capacity to take it.

Buy high, sell low

The laws of financial physics aside, this is arguably a generationally awful time to encourage pension funds to pile into venture or and private equity. This is where things get a bit complicated.

Private markets are still living off the fumes of 2021 prices. The bulk of capital raised by venture came in 2019–2021, when interest rates were near zero and valuations hit historic highs. Those funds are now fully invested but largely unexited: their portfolio companies haven’t IPO’d, haven’t raised fresh rounds at lower prices, and haven’t yet been written down. Instead, they remain marked on fund books at inflated valuations. Yet in the secondary market – where investors actually trade these fund stakes – venture portfolios are clearing at sometimes in an excess of 25% below stated net asset value.

This might sound like a great opportunity to buy on the cheap – but it isn’t for pension funds. Under these reforms, schemes need to meet rapid allocation targets. But pension funds don’t usually buy these discounted stakes in funds on the private market directly; instead, they go through pooled access vehicles. This is because defined contribution pension schemes are operationally expected to offer daily-dealing funds, meaning savers can switch or withdraw at any time based on a daily unit price. Private assets don’t fit this model, as they’re illiquid, rarely revalued, and can’t be sold on demand.

A pooled access vehicle is an investment fund that sits between pension schemes and the underlying venture capital or private equity funds. It gathers contributions from multiple schemes, keeps a small cash reserve for day-to-day withdrawals, and spreads the rest across dozens of illiquid investments. Because those investments are not traded every day, the vehicle re-values them monthly. It then converts that figure into a daily unit price so members can see a price and move their money if they wish – even though the published price may lag the level at which the assets could actually be sold.

The pooled access vehicle is not incentivised to deviate significantly from the valuations reported by the venture funds they’re invested in. In a quiet market with few exits, valuations stick, even if market conditions have changed. If a company last raised a round in 2021 and no new financing has occurred, there’s nothing stopping a venture fund from marking it at the same valuation, even if comparable companies have halved in value. So if the fund’s valuation is stale or inflated, the pooled vehicle simply inherits it, and passes it through to DC savers via the daily price.

Unlike DC pension funds, endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and other investors view private market marks as an internal accounting convention rather than a trading price: they do not owe daily liquidity to anyone. A sudden 30% markdown doesn’t flow into a unit price, and they can absorb the hit in multi-year performance figures.

This means that any pension capital moving into these vehicles today risks inheriting that overhang and paying close to full price for assets the market is already repricing downward. Instructing a group of large funds to move into the space in lockstep all but guarantees it, flooding the market and reducing any leverage they might have. For pension savers the timing risk is acute. Funds raised at the end of easy-money cycles (1999-2000, 2006-07) delivered the weakest long-run returns once valuations normalised.

This mandate cushions professional investors in underperforming funds, while transferring the looming markdown to ordinary savers who want cash at retirement. Socialising the downside of the finance industry isn’t fair or efficient.

1) Bid up prices 2) ??? 3) profit

It’s hard to detect a serious theory of change in the review. My best guess from reading is that it’s something like this:

By pushing every auto-enrolment scheme into at least one £25 billion vehicle, big-fund buying power will shave a few basis points off charges, giving trustees enough bandwidth to run complex, illiquid mandates.

This will channel billions into new ‘productive’ assets, which will boost returns for savers and unlock £50 billion of fresh capital – half of which would go into the UK.

The IPOs of these venture-backed firms will in turn fire up London’s equity markets, boosting growth and productivity.

As established above, this will in practice involve paying more for access to a distinctly mixed bag of private assets, while holding out for a speculative 2% improvement in long-term performance.

Meanwhile, the £50 billion headline figure seems charitable. It assumes:

DC assets will grow at 17% a year (optimistic based on current trends).

40% of all current private market exposure pension funds hold is UK-based (currently only true for a minority of funds’ allocations)

Every fund will hit its allocation target.

Hitting the review’s headline UK goal will mean channeling £5 billion of new money a year for the next five years into companies or projects. At the moment, we have about £2-3 billion going into UK infrastructure schemes and about £600 million going into private capital from UK pensions. Doubling this overnight will inevitably bring distortion. In the meantime, funds will need to secure another £25 billion of allocation internationally, competing against peers, endowments, and sovereign wealth funds to get into the best deals.

It’s also unclear why these listings would boost London’s equity markets. Even if we did create a successful new generation of UK start-ups, there’s nothing stopping them listing in the US, with its deeper capital markets. I will confess to being personally indifferent to this question. The health of the London Stock Exchange makes little difference to the performance of the wider UK economy. Meanwhile, countries like Israel manage to have successful technology ecosystems, even though many of their successful companies list on Nasdaq. Either way, the government just … assumes this will happen.

It’s tempting to look at the examples of Canada and Australia and to say that we’re bringing the UK in line with international best practice. The difference is, these funds commit to venture because their boards believe the risk/return is attractive, and they spread those bets across Silicon Valley, Israel, China and Europe. They aren’t responding to a government quota anchored in a single, mid-sized venture ecosystem that forces buying even when pricing or deal quality is poor. This is the opposite of how successful overseas funds behave!

Closing thoughts

Behind both the review and successive governments’ haranguing of the pensions industry it’s hard to miss the air of desperation. Amid dismal levels of domestic investment, shrinking capital markets, and chronically weak domestic productivity, the Treasury has decided to conscript the pensions pool as an emergency ballast.

Government has fixated on venture as a potential public policy lever for a while, hoping that with enough taxpayers’ money, it can create a cargo cult Silicon Valley. At the end of the day, venture capital funds are as much a part of the finance industry as any other form of investment vehicle. They aren’t uniquely patriotic, productive, or free of vested interests. Middling fund managers are middling, regardless of whether they buy stakes in start-ups, public companies, or trade coffee derivatives.

As ever, the government appears desperate to avoid confronting any of the tax, listing or planning reforms that make private capital hesitant, instead reaching for the sugar hit of other people’s money.

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views only. They are not the views of my employer, any pension fund managers, or trades of coffee derivatives. Do not take financial advice from strangers’ Substacks. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

GREAT analysis - as always