Rearranging the deckchairs

Flashy nuclear and AI ‘investment’ deals don’t fix fundamental problems

Visits from foreign heads of state see the robotic UK government comms machinery at its most Pravda-esque. During President Trump’s visit, press releases from Gov.UK GPT announced “record-breaking” £150 billion investment into the UK to “catapult” growth and “deliver opportunity for working people up and down the country”, a “world-leading Tech Prosperity Deal” will usher in a “Golden Age of Innovation”, while “British families will also see even stronger energy security” as part of a “Golden Age of nuclear”. Tractor production up 500%, comrades!

Much like the Five Year Plan, the numbers look much less impressive on closer inspection.

The £150 billion figure is a great example. £100 billion of this comes from US asset management giant Blackstone. Setting aside that 10 of the £100 billion had been announced over a year ago, the “investment pledge” amounts to Blackstone stating they plan to invest this sum in UK assets over the next decade. There’s no concrete commitment or contract. All, some, or none of this money may actually materialise.

Recently, I wrote about how the government’s tech, environment, and infrastructure policies don’t align. Announcements about new data centres are all very well, until you find that you’re unable to connect them to the grid.

A lot of people in the Progress extended cinematic universe were understandably enthused by a run of nuclear-related announcements last week, including new corporate deals and plans to streamline design approvals.

Separately, the Jensen Huang Show also came into town to dazzle audiences with a rush of AI infrastructure pledges.

So, should working people up and down the country brace themselves for the Golden Age of Nuclear and the delivery of the accompanying opportunity? Spoiler alert: not yet.

The nuclear announcements

Last week’s nuclear announcements fell under two headings.

The first was a set of commercial partnerships:

X-Energy and Centrica – will build up to 12 advanced modular reactors in Hartlepool.

Holtec, EDF and Tritax – will develop small modular reactor–powered data centres at the former Cottam coal plant in Nottinghamshire.

Last Energy and DP World – will build a micro modular nuclear plant at London Gateway port.

Urenco and Radiant – will provide £4m in HALEU fuel supply to the US, with Urenco developing an Advanced Fuels Facility in the UK.

TerraPower and KBR – will study and evaluate UK sites for deployment of Natrium advanced reactors with integrated energy storage.

Second, the UK’s Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) and the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission signed a refreshed memorandum of understanding (a non-binding agreement) designed to streamline regulatory licensing.

Moving at a snail’s pace

If you want to build a small modular reactor (SMR) or a micro reactor in the UK, you need to have a reactor design that works, some people prepared to pay for it, and the regulatory approvals to build and fuel it.

The UK has never licensed or built an SMR before and only a small handful exist anywhere in the world. Rolls-Royce recently won the Great British Energy – Nuclear competition to great fanfare, with the official announcement declaring it a “new era for nuclear power”. This means it is the ‘preferred bidder’ to build new SMRs in the eyes of the government, which makes accessing subsidies easier, but doesn’t actually expedite any approvals. The company currently envisages connecting its first reactors to the grid in the mid-2030s.

This seems appallingly slow. Rolls-Royce has long manufactured pressurised water reactors. While there will be important technical differences relating to scale and uranium enrichment levels, the company should have the supply chain, skills, and the safety culture to build an SMR faster than anyone else. It recently reached the third stage of the ONR’s Generic Design Assessment process, ahead of schedule. The GDA is essentially a way for developers to get buy-in from the regulator to their design before they apply for a licence for a project on a specific site.

So why is it taking another decade?

In short, the UK’s current policy is that a small reactor should be regulated in the same deeply conservative and inefficient way as a gigawatt-scale reactor. The ONR’s director of regulation for new nuclear reactors, has said that “there isn’t any difference; the regulatory regime is technology agnostic”. The notion that a 20-megawatt reactor needs to be subjected to the same scrutiny as one like the 1.6-gigawatt reactors being built at Hinkley Point C, despite the significantly smaller risk profile, seems perverse.

Unfortunately, the regulatory regime for UK nuclear reactors is among the most conservative anywhere in the world, where new nuclear power isn’t actually banned. A reactor will go through a process that will last a minimum of eight years before they can start work on construction would last 18 months for a comparable project in South Korea.

Much of this stems from the UK’s unusually conservative interpretation of international radiation safety principles. For example, the UK instructs developers to reduce risk “as low as reasonably practicable” (ALARP). This means that any measure that is not “grossly disproportionate” must be introduced. The UK refuses to have reactor, design-specific rules, or ‘safe’ level of radiation, which means that developers are often left trying to second-guess an inspector’s interpretation of rules, past precedent, international best practice, and … vibes.

The ONR has an extended track record of requesting trivial but expensive changes to designs that function in other countries, whether it’s unnecessary amendments to filtration systems or huge increases in the volume of concrete and steel.

I’ve written elsewhere about the poor evidentiary basis for measures that drive down already trivially low radiation doses.

In the absence of significant regulatory reform, things begin to look tough for some of the projects involved in this announcement.

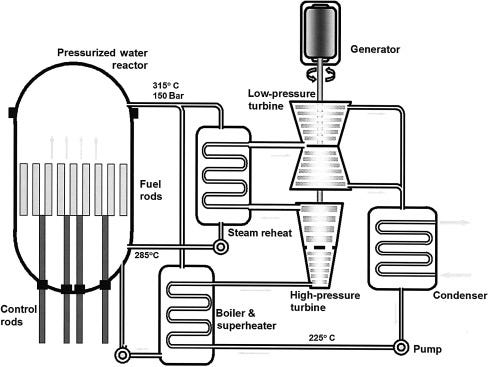

Roughly 80% of the reactors operating in the world are pressurised water reactors. Rolls-Royce is designing a PWR, while EDF is building PWRs at Hinkley Point C and Sizewell C. Sizewell B, the last reactor to be built in the UK, is also a PWR.

PWRs basically work like old coal or oil plants, but with a different fuel: water is boiled to produce steam, which spins a generator. This is pretty straightforward, but a lot of the heat goes wasted. If you want to read more about reactor designs, take a look at this.

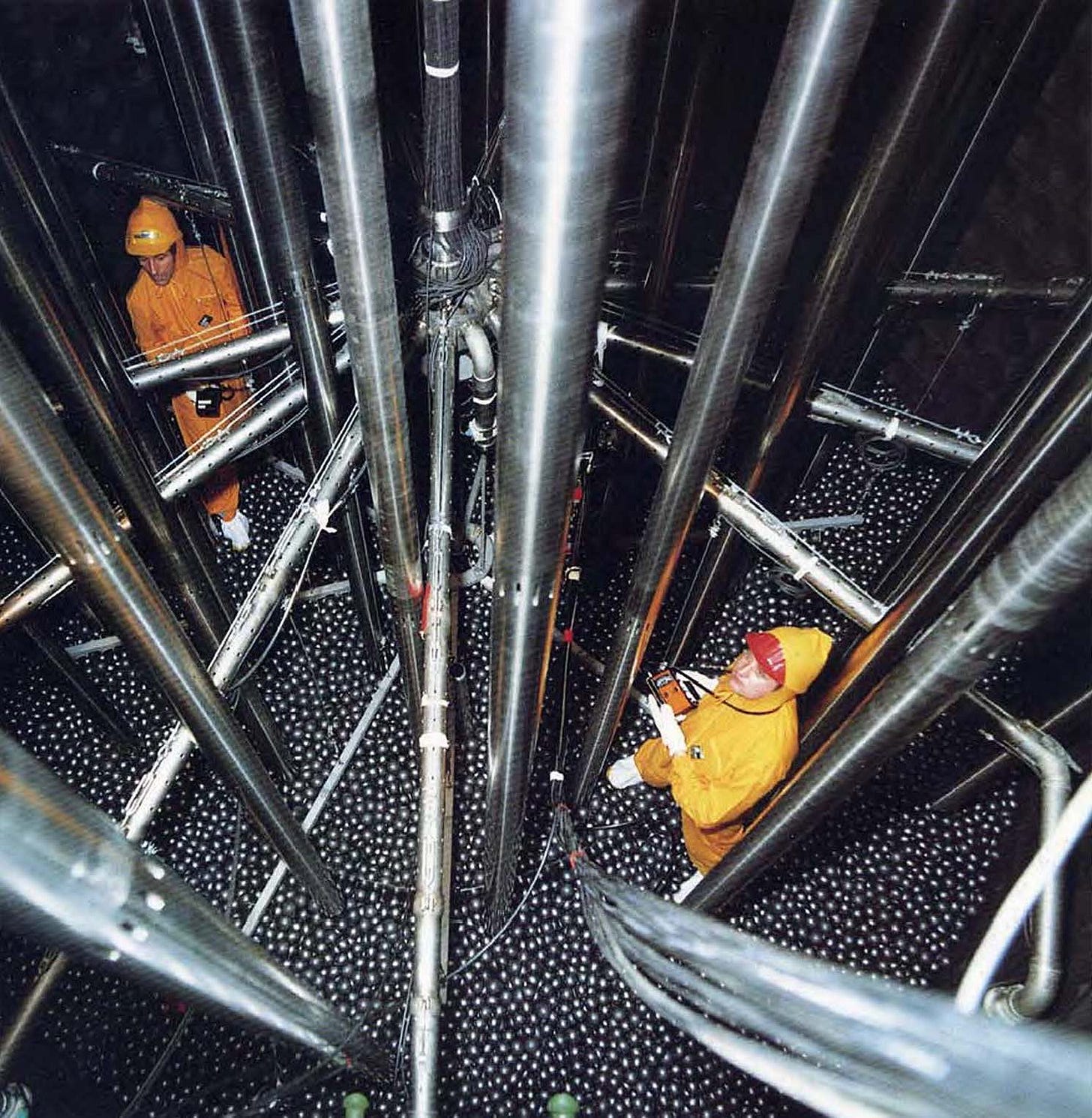

A number of SMR designers are attempting to build more efficient reactor designs. X-Energy, who are partnering with Centrica, are trying to build a high-temperature gas-cooled pebble-bed nuclear reactor. In one of these reactors, the fuel is packed into thousands of tennis ball-sized graphite spheres. Helium gas flows through the spaces between them to carry away heat. Helium is chemically inert and remains gaseous at high temperatures, meaning the reactor can operate safety at very high temperatures, significantly boosting efficiency.

This is technically impressive, but phenomenally challenging. The one such facility operating in the world is a demonstrator in China, where the nuclear sector is nationalised and given exceptionally favourable regulatory treatment. The only other pebble-bed reactor built with a similar design was a 1969 experimental plant in West Germany. Plagued by technical failures and extended outages, the small 15-megawatt unit was dubbed ‘the shipwreck’ in German nuclear circles, and it was decommissioned in 1988 after fewer than 20 years’ service.

I’m not saying that companies shouldn’t build high-temperature gas reactors or that the X-Energy design is bad. But in the absence of sweeping reforms, it seems implausible that this design could successfully run the gauntlet of UK nuclear regulation and be built before the 2040s.

The company has only completed one stage of pre-application engagement with the ONR. This tier is a single day event with the regulator, where they explain the process to a prospective applicant. This hasn’t stopped the company claiming that work will start in 2026 for deployment in the mid-2030s – roughly the same time frame as Rolls-Royce.

I’m going to skip over the TerraPower/KBR announcement, as it is a very vague commitment to think about building an experimental design in the UK. It feels like corporate marketing the government has bundled into an announcement to bulk it out.

The Holtec/EDF and Last Energy/DP World announcements seem like altogether more serious proposals. The Holtec design has passed stage one of the Generic Design Assessment, while Last Energy has cleared the Preliminary Design Review (the last state of engagement before making a formal site licence application). Both companies have therefore meaningfully engaged with regulators in the UK. They are also both building PWRs, which means that they are taking on significantly less technology risk than X-Energy.

In a sane world, it should be possible to build these reactors quickly, but projects still potentially face an eight year march through the UK nuclear site licensing and planning system. In essence, the government remains the biggest obstacle to its own golden age.

These points aside, the individual projects also have problems to navigate. For example, EDF and Holtec picked the Cottam site for a few different reasons. As a former coal-fired power station, it has some obvious advantages from a planning standpoint and a substation for grid connections.

Unfortunately, for EDF, the substation is taken. While they used to have a grid connection at Cottam, the capacity has now been assigned to a solar and battery project. This means that they will likely have to join the same decade-long queue as any other project.

Moreover, Cottam is not a coastal or estuary site. This means EDF and Holtec will need to rebuild the old cooling towers, which were demolished … a month ago. The alternative is directly tapping into the Trent for cooling, but this would involve an unenviable political and legal battle with environmental groups.

The Last Energy/DP World project is for a significantly smaller reactor (20 megawatts versus 300 for Holtec) and the design can use air cooling, which means it doesn’t have to navigate the tower versus river conflict. The project is being pitched as a private wire project, which means that the reactor will directly power the London Gateway port that DP World, a multinational logistics company, operates.

But that doesn’t make things easy. In a country like South Korea, or France during its rapid buildout, once a design is deemed ‘safe’, it’s much easier to build it at multiple sites as part of a ‘fleet-based’ approach. In the UK, you have to navigate the process on a project-by-project basis. The DP World project is Last Energy’s second proposed site. They still need to secure approval on their first planned project in South Wales.

Mutual recognition?

It’s against this backdrop that we should treat the ONR’s refreshed memorandum of understanding with its American counterpart with a degree of scepticism. The agreement states that the two wish to cut approval times for new reactors, aiming to finish design reviews in two years and site permits in one. To do this, they’ll divide up review work, make use of each other’s past assessments, and, where possible, accept one another’s conclusions.

The memorandum itself notes that regulators in both countries have had a cooperation agreement since 1975 and they, in fact, signed another agreement last year (along with Canada) to cooperate on advanced reactor approvals. This document already contained a number of commitments for the regulators to facilitate information-sharing and develop shared regulatory approaches that mean the approvals process in one country will produce documentation that helps answer the questions raised by a similar process in another.

The only novelty is the non-binding time targets and some slightly stronger language on mutual recognition. Even then, the ‘mutual recognition’ will only come after “appropriate due diligence”, which gives regulators essentially unlimited leeway to negate anything that the agreement might be hoping to achieve.

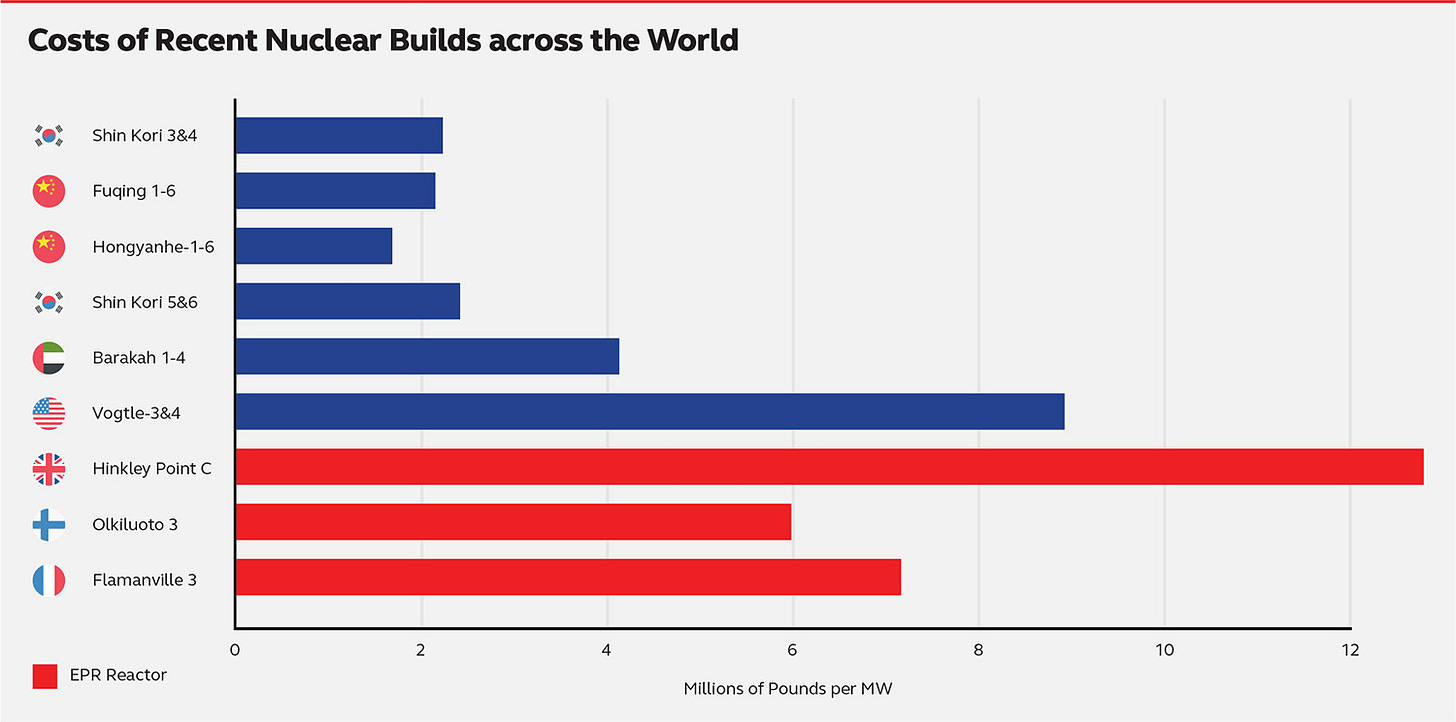

Real mutual recognition would be a welcome step forward, but nuclear regulation is bad … basically everywhere in the western world. Vogtle 3 and 4, the newest US commercial reactors, are among the most expensive ever built. Better than the UK’s attempts, but still dismal.

Aligning ourselves with regulation that allows nuclear power to be built at a marginally less catastrophic price is an improvement, but it’s not a substitute for rethinking regulation from first principles. If you want to read some more transformative ideas, my friends at Britain Remade recently published a serious playbook that covers science-based radiation rules, measures to streamline planning and environmental rules, and steps that would unlock a ‘fleet-based’ approach.

Spinning out of control

If there are question marks over the golden age of nuclear, the AI side of the UK’s great infrastructure build is raising some interesting questions.

The UK Government and NVIDIA jointly announced that the company would be deploying up to 60,000 GPUs in UK-based data centres by the end of 2026, with the total number potentially reaching 120,000 over the next few years. Tom Bristow at Politico dug into the numbers and found that the NVIDIA and DSIT press offices got a touch excited and the number was closer to 30,000.

During his visit, Jensen Huang said that nuclear power and gas would be required for the UK to meet its AI ambitions. In our last piece, we covered some of the uncertainties hanging over how AI Growth Zones would be powered, with some in government lobbying to limit the role of fossil fuels and instead rely on wind and solar. We now have a clearer idea, with the newly announced one gigawatt ‘Stargate UK’ project relying on diesel generators for back-up. Given the UK government shows no sign of backing down from its highly ambitious plan to transition 95% of UK energy generation to green sources by 2030, something is going to have to give.

The only hope is that the UK Government’s Nuclear Regulatory Taskforce follows through on its punchy interim report with a set of sweeping proposals for reform and the government takes them seriously.

Otherwise, it’s going to take more than Pravda headlines for the UK to back itself out of this one.

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views only. They are not the views of my employer, any West German nuclear engineers, or anyone else. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

So as someone who has recently read Stephen Smiles’s book on George Stephenson who created the British railway system, I have to conclude that this is all self-induced. Basically, in England, the only law is Parliament is Sovereign, and so they could pass a law tomorrow saying “this will be built, screw the existing regulators and laws.” Which is how the railways were built. But they don’t, meaning that this is all pointless runaround, millions of wasted man hours in a pointless system that exists essentially to block nuclear reactors altogether.

Love this!