The UK goes nuclear

At last, some … good news?

Introduction

I’ve written before about how the UK is running contradictory technology and climate policies and how I think nuclear power is the only way out of this. If you want to understand why wind and solar are not the way forward for us, Dieter Helm has written an excellent explanation.

Early nuclear buildouts, such as the UK’s in the 1960s and France’s in the 1970s–80s, saw reactors approved and constructed within five to six years. These designs were smaller than modern reactors and significantly less complex, but had a strong safety record. Calder Hall, switched on in 1956, was built in three years and safely generated electricity until decommissioning in 2003.

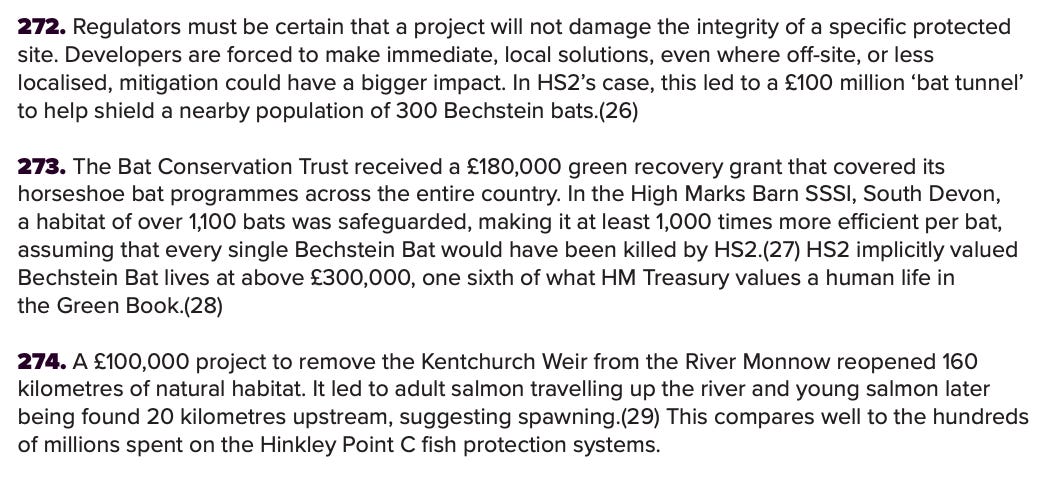

Unfortunately for enthusiasts, the UK’s attempt at a nuclear renaissance has been pretty shambolic so far. Hinkley Point C, which is currently under construction, is set to be the most expensive power station built anywhere in the world ever. The project is running 16 years behind schedule and about £17 billion over budget. Sizewell C, despite being built with an identical design, is set to be even more expensive to construct, though since it has a cost-plus contract, and is 45 percent government owned and funded, it may spend less on interest payments than Hinkley, where the private sector took on all the risk and debt.

While reactors are still built at pace in South Korea, China, and the UAE, things have become slower and costlier nearly everywhere else. But the UK has the dubious honour of being the most expensive place to build a nuclear power station in the world. And it’s not even close. Much of this in my view is driven by politics rather than science.1

Against this backdrop, the government commissioned an independent taskforce earlier this year to produce recommendations on how to streamline the process. The taskforce, chaired by regulatory expert John Fingleton, published its findings today. In a rare positive Chalmermagne post, I think this is a rare example of a government review that has the potential to be transformative.

What went wrong?

To understand why this report is important, you need to understand just how bad the situation is at the moment.

There is no single regulator or unified process for approving a nuclear project. Instead, developers must secure a nuclear site licence (itself made up of several layers of independent approvals from different bodies), multiple environmental permits, and full planning consent. Each regime evolved in isolation through decades of legislation and case law. Each of the three is individually conservative, but they also overlap, resulting in significant duplication of effort and documentation.

Hinkley Point C is instructive. EDF sought to build the European Pressurised Reactor in the UK, a design created with Siemens in the early 2000s to exceed public expectations on safety. For example, it had four emergency cooling and power systems, twin thick concrete shells (one of which could withstand the impact of a fully loaded passenger jet), and a steel-lined core catcher. EDF modelled the probability of core damage at one in ten million reactor years – an order of magnitude lower than the industry standard. As a result of the UK’s regulatory process, they had to make 7,000 design changes, which added 35 percent more steel and 25 percent more concrete.

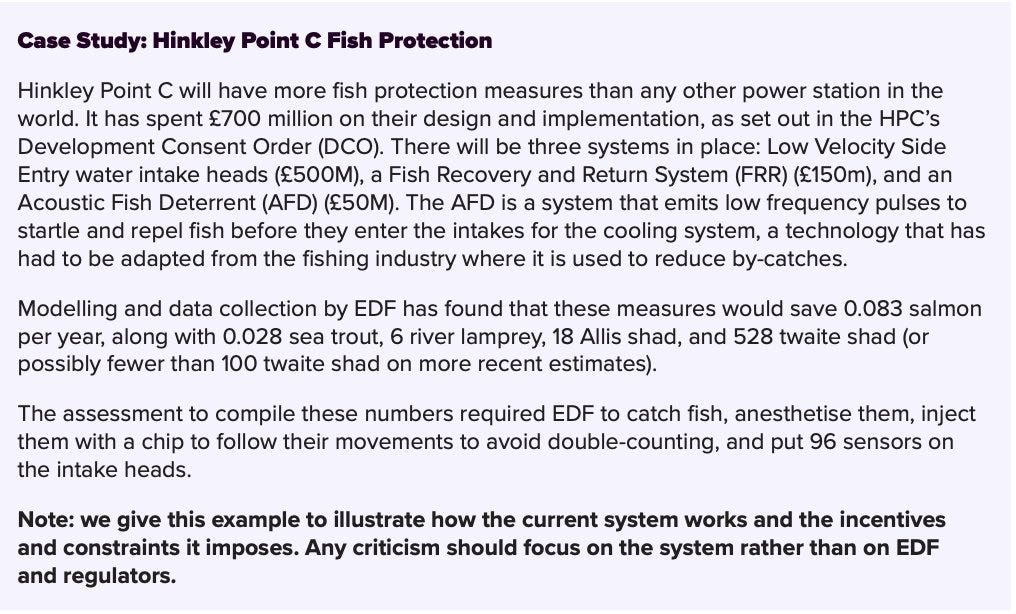

After satisfying the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR), EDF produced a 31,401 page environmental statement and seven Habitats Regulation Assessments. They had to mitigate any potential environmental harm that they could not incontrovertibly rule out.

The most notorious example is the hundreds of millions of pounds that EDF had to spend on fish protection, in case fish entered the intake vents for the plant’s cooling system. This included a system to retrieve and return fish and an acoustic fish deterrent that would blare out low frequency pulses to scare the fish away. Despite EDF appealing the latter on the grounds that there was no danger to any protected species of fish, a government inspector demanded that EDF press ahead on the grounds “it cannot be concluded that there would not be adverse effects”. In other words, the developer had failed to prove a negative.

Layered on top of this was a sea of other permits. For example, permission to place a diesel generator onsite during construction or licenses for dredging and soil disposal. Each of these involved separate consultations and sets of conditions. The Environment Agency’s 2023 amendment of the water discharge permit alone drew 243 consultation responses and a 120-page decision document.

Much of this documentation is the product of legal risk, rather than the rules themselves. Environmental impact assessments for major projects used to be much shorter: the 1993 Jubilee Line Extension required only a few hundred pages. Since 2001, however, the UK has been bound by the Aarhus Convention, an international treaty that is meant to secure public access to justice on environmental issues. This caps claimant costs in environmental judicial reviews at £5,000 for individuals and £10,000 for groups.

When litigation is very cheap, it encourages speculative challenges from anti-development groups that hope to catch projects out on technicalities. Developers respond by producing enormous volumes of documentation to minimise legal exposure. Hinkley has defeated three such challenges; Sizewell C has beaten two and is fighting a third.

How we fix this

Given that no one ever set out to design this system, John Fingleton and his team have done us all an immense favour by taking the time to piece together, what they call, the ‘system failure’.

They have also proposed some genuinely radical measures. The proposals in this report won’t get us down to Chinese or South Korean costs and timelines, but they’ll bring us in line with countries like France or Finland. It’s not the promised land, but it could mean nuclear costs dropping by as much as 50 percent.

There’s a lot in this report and it’s pretty accessible, even if you don’t follow nuclear. I’m going to focus on a few measures that have the potential to be particularly impactful.

Streamlining regulation and improving incentives

To stop several bodies regulating the same issue, the Review proposes designating a lead regulator for every project, which coordinates all regulatory input and resolves tensions between agencies. It also recommends simplifying responsibilities so that each category of safety or environmental issue is handled by a single authority rather than being shared.

Longer-term, it proposes creating a Commission for Nuclear Regulation. This would sit above ONR, the environmental regulators and planning bodies and act as the final arbiter on big cross-cutting decisions, rather than leaving projects to negotiate between half a dozen separate authorities.

There are also some hard-edged proposals around ensuring proportional decision-making. When regulators aren’t obliged to account for time and cost, it incentivises them to pile endless requirements onto other people. As a result, the report recommends amending secondary legislation so regulators have to consider “the cost, time and difficulty involved” when requesting changes during the licensing process. On the environmental side, developers would publish high-level cost estimates for assessments and any mitigations over £500k. The decision-maker would then have to decide whether that mitigation is proportionate and to explain why it does not discourage future development.

Ending disproportionate conservatism

The Review argues that safety regulation has drifted into a pattern where the regulator drives already minuscule risks even lower, well beyond what international norms or scientific evidence require. It notes that ONR’s own dose targets sit far below natural background radiation, sometimes by two orders of magnitude, and below the internationally recommended levels used for medical and industrial radiation. This results in designers adding more systems and complexity simply to shave hypothetical doses that are already negligible.

The report cites an example I’ve dug into before about how the ONR forced GE-Hitachi to add a pointless set of extra filters into their proposed design’s ventilation system, which cut radiation emissions by one ten-thousandth the legal dose limit.

To reverse this, the Review proposes that the government – not the regulator – should define a clear national threshold for what counts as a tolerable level of nuclear risk. Once that threshold is set, ONR and the Environment Agency would be formally instructed that risks below that line are already acceptable, and that further reductions should only be sought when there is a concrete, proportionate reason.

No more praying to the environmental rain gods

The Review contains a lot of sensible recommendations on bringing sanity to the environmental assessment process. If implemented, these would cut down on the number of reviews and strip out the need to mitigate completely hypothetical risks (e.g. “you can’t prove that X species of bird wouldn’t be disturbed in Y highly implausible way”).

More radically, it offers an alternative route to the existing system. At the moment, developers normally need to mitigate any environmental effects on site. This can often produce convoluted and ineffective interventions. As the report points out:

Instead, the report proposes the creation of a new national nature recovery fund, run by Natural England. In exchange for paying into the fund, developers could set aside surveying and permitting requirements. The idea is that this fund could support genuinely impactful habitat improvements at scale, rather than focusing on site-by-site measures.

Curbing legal risk

My personal preference would be for the UK to simply leave the Aarhus Convention. Despite our exceptionally generous system of cost caps, the UN consistently claims we haven’t gone far enough. The question of membership, however, sat outside the scope of the review. Instead, the authors have done their best to cut back legal risk within this constraint.

Firstly, the Review suggests linking the cost cap to inflation. The £5,000 and £10,000 figures were set in 2013. If we’d increased them in line with inflation, they would sit at £7,000 and £14,000. Still too generous, but better than nothing.

More importantly, it recommends allowing courts to lift the cap altogether if they believe that judicial review has been abused. If you are an aficionado of planning judgements, you will occasionally see judges’ frustration shining through. For example a Court of Appeal ruling from earlier this year on a challenge to a power station described the claimant’s approach as “a classic example of the misuse of judicial review in order to continue a campaign against a development [...] once a party has lost the argument on the planning merits.” They were unable to punish this at the time, but this may change for future cases.

In October last year, a separate review into legal challenges against nationally significant infrastructure projects recommended moving to a ‘single bite of the cherry’. This means that claimants can only litigate a specific issue once. If you challenge the awarding of a nuclear site licence and are unsuccessful, you shouldn’t be able to challenge the decision to grant planning permission using the same set of facts. Despite welcoming the review, the government hasn’t enacted this yet. This is an opportunity to correct this.

The review also has some interesting points on incentives. At the moment, if a project is challenged, developers often down tools. If a permit or planning permission is revoked, this could involve spending millions to unpick work. The review suggests indemnifying the developers of critical national infrastructure so that in the unlikely event that they are defeated, they won’t have to pick up the tab for work they have already started.

What’s next?

The government will respond in full to the recommendations on Wednesday as part of the Budget. It is vital that they accept all of them unambiguously – it’s the only way of slicing through the Gordian Knot.

As one friend of mine in the industry put it: “I can’t stress enough that whether these recommendations are implemented is the difference between nuclear being functionally illegal and so requiring me to become American to build on the one hand, and on the other hand our country having a genuine chance at becoming a nuclear power again.”

There are already rumours that officials are seeking to water down the more radical ideas and they will undoubtedly face concerted lobbying from environmental groups and others.

If the government says that it’s accepted ‘the majority’ or even ‘the vast majority’ of the recommendations, the red lights should start flashing on the dashboard. As in any review, there are a small handful of mission critical policy changes, alongside a greater number of more minor tweaks. It is very easy to imagine a world in which the government accepts the latter while watering down the former.

We’ve already seen the government gesture at nuclear reform in a not entirely convincing way, so this is its opportunity to demonstrate seriousness.

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views only. They are not the views of my employer, environmental NGOs, nuclear safety inspectors, or anyone else. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

After all, Chernobyl happened with a shonky Soviet reactor design that didn’t have a containment dome, while repeated studies in the area around Fukushima found no evidence of adverse health effects.